I grew up in Rezé (near French Bretagne), where one of the 5 Unités d'Habitation was built, designed by the famous Swiss-French architect Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, as known as Le Corbusier.

Le Corbusier designed the Unités d'Habitations after World War II, as utopian cities within a city where tightly-knit communities could access everyday life services within the building itself. These massive skyrises would host hundreds of (mostly) lower income families, as well as shops, restaurants, sports, and medical facilities. The top floor of the buildings would accommodate a kindergarten school, where I was lucky to be studying in the early 1990s.

In spite of my young age at the time, I keep vivid memories of the bold shapes and colors that defined this post-war architecture. I also remember witnessing its flaws. Although they were deeply attached to the building, families and friends were constantly grumbling about its grim concrete facades. As years passed, I started realizing that very few concepts from Le Corbusier's original designs were still alive. None of the businesses were running anymore. The sports facilities were totally abandoned. I would never get to swim in that fancy rooftop swimming pool. While the building's community was certainly as vibrant as Le Corbusier envisioned it, the autonomous city he dreamt of was not functional. What could explain the semi-failure of what originally seemed to be a clever solution to the post-war housing crisis?

As it turns out, the community was never able to fully appropriate the space it was living in. It appeared that public housing—spaces for all—required more than a design vision: it needed to interact and evolve with its people. By creating such a heavily designed environment, Le Corbusier built a house that failed to become people's home.

The Cité Industrielle (Tony Garnier, 1917) is a socially utopian city plan applauded by Le Corbusier in the periodical L'Esprit Nouveau

20 years have passed and I've grown to become an interaction designer, which can be thought of as an architect for virtual spaces. Because the public expects their online experience to always become more immersive and connected, I end up spending a lot of time thinking of how to bring the qualities of physical space into the virtual world. In fact, I always compare the social experiences I create to their real-life counterparts. This analogy can sometimes feel frustrating.

On one hand, expression in the real world seems limitless. We connect with people through rich variations of speech, body language, and interactions. Through appropriation and creativity, physical space enables us to develop intimate bonds with our communities. Sometimes it also allows us to express ourselves through subversion, from graffiti to street protests. Limits around our behavior are mostly defined by social norms and consent.

On the other hand, expression in virtual space can feel limited, disconnected, and dehumanized. As we scroll through endless streams of content, interfaces make it hard to feel other people's presence in any real way. On media sites, what could be a shared reading experience with thousands of our peers is in fact a very lonely one. The only pretense of social interaction is relegated to the bottom of the page, in a comment box where everyone writes, but very few read. Even on the most socially interactive platforms like Instagram or Twitter, the only glimpses of human contact are mere likes and comments popping up in a notification panel.

Language itself is reduced to its most basic and brutal form. We struggle—I struggle, maybe I'm getting old—to express basic concepts with hundreds of emojis that hardly convey the depth of our emotions. Speech feels gradually more normalized as social apps revolve more and more around constrained communication forms. As of today, the most popular platforms grant us a maximum of 140 character messages, 10 second videos, and a handful of filters.

The full range of human emotions - Facebook.com

These forced constraints dehumanize our communications to the point that it often feels like we are talking at each other rather than engaging in actual conversations. Image boards and comment sections on media sites are filled with hatred. Social platforms seem to encourage flame wars, trolling, and harassment of minorities. It is often pointed out that people express things online they would never dare to say in real life. Is it because technology reveals our inhumanity, or rather because it distorts our relationship to others?

One could argue these differences between physical and virtual communications are inherent to digital media. Conversely, I believe it is a byproduct of our design approach. In the same fashion modernist architects believed they could revolutionize people's way of living with one-size-fits-all housing concepts, technologists try to accommodate the entire spectrum of human communications with highly controlled social media platforms. By over-designing these spaces, both professions have hindered the public from appropriating them.

Le Corbusier aimed at creating better living conditions and a better society through authoritarian design. He tried to force his political views onto people's lives, and ended up creating dysfunctional architecture that was disconnected from their aspirations. Society eventually moved away from this approach; I believe it needs to follow a similar path with digital media. Technologists should not design human expression, but facilitate it.

Unsurprisingly, highly controlled software is designed in highly controlled environments

Sebastian Bergmann - Google Campus - License CC BY-SA 2.0

How can we enable people to appropriate the social platforms we develop? This kind of agency is hard to emulate in a digital world where every feature requires a lot of development work. However, with a thoughtful use of existing technologies and empathy, I believe we can make the web feel more humane. After all, email, the most intimate and popular form of online communication, is also the simplest. The following are a few principles and examples suggested as ways to revisit social media.

Firstly, small interventions can enhance social media to feel more intimate and relatable. Friends in Space, a social experiment by New York based studio Accurat, shows how minimal and poetic interactions can make millions of people feel connected across the world. What if, similarly, you could sense other readers' presence through their clicks, scrolls, and cursor moves on this very essay?

Secondly, allowing appropriation is also enabling subversion. In Spring 2014, Carnegie Mellon University student Joel Simon released FB Graffiti, "a chrome extension that exposes every wall post and photo on Facebook to graffiti." Upon installing the application, users are invited to anonymously deface their friend's pictures by drawing on them. It encourages users to reclaim their personal data in a way that escapes Facebook's control.

Finally, as we imagine letting people reclaim their experience of social media, we could go further and consider a true decentralization of virtual spaces. Projects such as the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS), Ethereum, and Webtorrent aspire to replace standard web protocol HTTP with peer-to-peer based technologies that redefine the way we distribute and consume data. If these have obvious benefits from an infrastructure point of view, they also unlock a wide range of new exciting use cases, from personal data licensing to user-powered content distribution.

If technologists move towards a more humble way to facilitate human interaction, maybe will we see a power shift in users’ experience of the internet. In a web where social platforms are designed as empowering infrastructures instead of control systems, people could define their own way of living and interacting together. Who knows, we might be able to build a more humane version of the Ville Radieuse Le Corbusier was dreaming of.

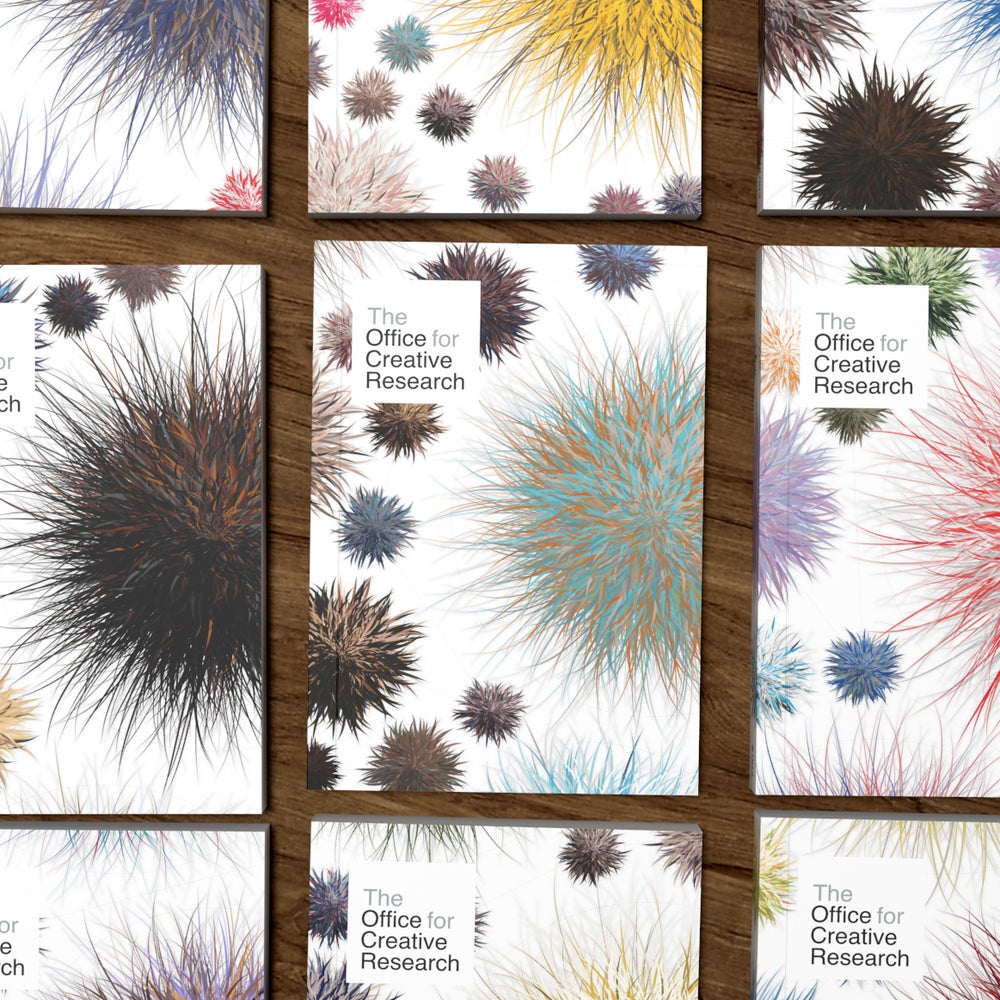

This essay was published in The Office For Creative Research’s quasi-annual journal, OCR Journal #002. It is now available for purchase. You can also read more essays from the OCR on Medium.

Special thanks to Sepand Ansari who directed me to Lev Manovich's piece after this essay was published.